The Evolution of the American Theater

To mark the anniversary of this legendary drawing, now in the Harvard Theater Collection, we present an excerpt from The Hirschfeld Century (Knopf) by David Leopold

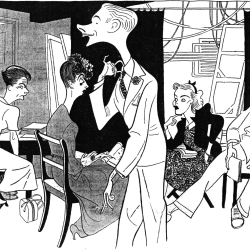

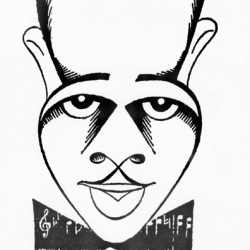

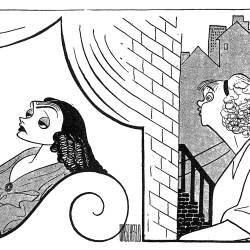

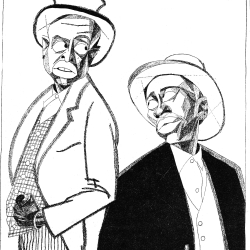

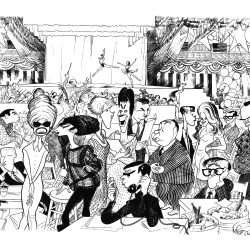

On Sunday March 25, 1945 in the Times, top of the fold and just beneath the masthead, six days before Broadway would be introduced to their characters, Al included Julie Haydon and Laurette Taylor as Laura and Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie in a diptych with Katharine Cornell and Brian Aherne in the third (and final) revival of The Barretts of Wimpole Street, which opened the following night. Or as Al later put it, “On the left, the grand dame of Broadway, Katharine Cornell, playing Elizabeth Barrett Browning. On the right, a new poet to give the Brownings a run for their artistic money, Tennessee Williams, with his first Broadway production, The Glass Menagerie.” Unencumbered by what others would write about either show, Hirschfeld gave the two shows equal weight in his drawing, which in retrospect neatly summarizes the transition of the American theater that was occurring that week.

On the left, an elegant depiction of the two costumed stars playing a melodrama framed by curtains—obviously a classic theater experience. As the drawing seamlessly moves to the right, the curtains literally hit a brick wall, with a tenement setting in the background. The flowing lines in this half are not the sweep of curtains or the roll of the divan but clotheslines between apartment houses. Neither Al nor the Times’ readers were aware of what they were seeing on that Sunday morning, but the glamour of the stage was giving way to the grit of human drama. The larger-than-life characters of Cornell’s era were soon to be replaced by more intimate performances of a new style of actors in works by a new generation of playwrights.

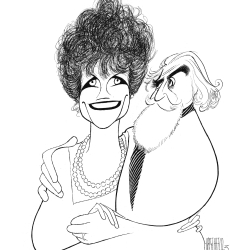

Katharine Cornell represented the long tradition of actor-managers who appeared in plays frequently written to showcase their strengths as performers. Cornell had been appearing in The Barretts of Wimpole Street since 1931 both on Broadway and on tour, the latter usually in repertory with plays by Shakespeare and Shaw. Even the classics were tailored to fit her bravura performing style, and audiences came to see her, her costumes, and the beautiful sets rather than the plays themselves. She was one of the last of the real troupers, along with Maurice Evans and The Lunts, who nurtured her company of sixty as well as audiences not just in New York and Los Angeles, but in Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City, St. Louis, Denver, San Francisco, and many smaller town in between. She had large expressive eyes under heavy lids, prominent lips, a small nose and a regal bearing. Perfect fodder for an artist looking a distinct image. By 1945, after nearly a quarter century on stage, Cornell could no more change her profile than her style and she remained wedded to her past successes. To Al, she has “invented herself” in both style and substance. Although her appearance was not as broad as Mae West or Ed Wynn, her look and performance style was just as distinctive which made her a pleasure to draw for Al..

Her contemporary, Laurette Taylor, an acting legend in her own right whose Broadway career had begun in 1909, had built a similar career, regularly appearing in plays written for her by her playwright husband and touring across the country and in London. Like Cornell, she had a remarkable presence on stage, and although the plays themselves were unmemorable, audiences for two decades flocked to see her perform. When her husband died in 1928, she virtually retired from stage and to alcoholism. Over the next seventeen years she appeared only twice on Broadway, and her return in 1945 was all the more surprising since the part in a new play by a new playwright was a serious role unlike any of her previous hits. By now Cornell was a benign dictator who maintained control over her large acting company, while Taylor at first forgot her lines in rehearsals and seemed unable to concentrate her energies on this small family drama. Nevertheless, Taylor and Glass Menagerie made a hit in, her final Broadway appearance in what was to be Broadway’s future. Cornell did enjoy a modest success with her show before touring the country, yet neither Barretts nor its playwright would ever again be produced on Broadway, while Tennessee Williams would have, at this writing, five Broadway revivals of his play, two Pulitzers, and numerous landmark plays, a handful of which are regularly revived on Broadway and around the world.

The era of the star vehicle and actor-managers was disappearing. Laurette Taylor, who died after eighteen months in The Glass Menagerie, ended her career with her greatest success, not in a role fashioned for her but one in which she breathed life into, absent any spectacular costumes or set. Even she recognized that it was the part—not the performer—that was important in this new work. When The Glass Menagerie opened to good reviews on tour with Pauline Lord as Amanda, Taylor telegrammed Williams: “I have just read the Pittsburgh notices. What did I tell you, my boy? You don’t need me.” Cornell soldiered on with her troupe and it’s special railcar. Her performances remained compelling, in some of the more out of the way stops on her tour, they had to last at least a year before she could come back, but her impact on Broadway started to fade, with her last two decades of performances and choice of plays more interesting as footnote rather than grand finale. On that Sunday in March 1945, Al preserved and illuminated the evolution of the American stage in the twentieth century, one that gives viewers, then and now, a real sense of the performance and personality of the actors who inhabited these roles.