Backstory in Black and White

By anyone’s standards, Al Hirschfeld and Duke Ellington were prodigious overachievers. Duke was born in 1899, Al four years later. The years 1927 to 1931 were particularly formative ones in the evolution of each man’s style, Al drawing caricatures for The New York Herald Tribune and The New York Times, Duke working at Harlem’s Cotton Club, writing exotic music for the club’s shows and breathtakingly original songs besides. Al’s progress in these years is visible in a legacy of hundreds of published drawings. Duke’s progress is audible in a legacy of hundreds of recordings his band made in these years for just about every record company in New York City.

Wall Street had famously “laid an egg,” but Ellington’s stock was very much on the rise. On September 20, 1930, NBC began a series of regular national broadcasts of the band from the dance floor of the Cotton Club that made Duke Ellington a household name from coast to coast. The band had visited Hollywood the previous month where they were filmed for RKO’s “Check and Double Check,” which premiered on October 25th. On February 5, 1931, Ellington commenced a long tour of motion picture theatres around the country, week-long engagements which saw the band working from morning to night, playing four or five sets a day punctuated by film programming. This became the band’s dominant mode of employment during the 15 years that followed, although there were also many “one-nighters” (usually dances), occasional residencies at hotels and clubs, and two trips to Europe, in 1933 and 1939.

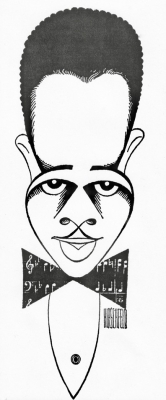

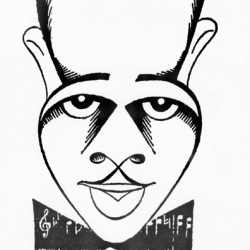

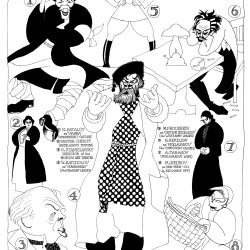

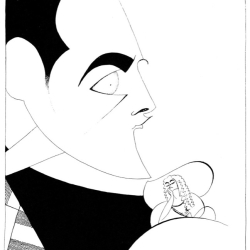

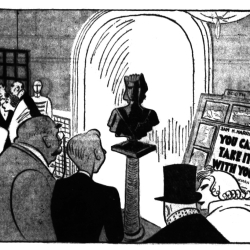

Hirschfeld’s earliest portrait of Ellington debuted in print on April 19, 1931 in The Des Moines Register above a caption that read “Duke Ellington, Harlem king of jazz, featured with his orchestra on Paramount vaudeville bill.” (A crude tracing of the design made by a different, unknown artist had appeared in an ad for the Paramount Theatre in the same paper two days earlier, the first of many inferior counterfeits that won’t be described here in greater detail. Grateful thanks go to a fellow Ellington researcher, Ken Steiner of Seattle, Washington, who located the first appearance of the caricature in a mountain of microfilms of vintage newspapers.)

Al’s iconic caricature was one of the most-frequently used designs in theatre ads for Ellington during the early and mid-1930s. The earliest-known “advertising manual” in support of a popular music act (analogous to a “pressbook” for a prestige motion picture) was created for “Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra” by staff at “Mills Dance Orchestras, Inc.” Internal evidence establishes a November 1931 publication date. It consists of 23 pages of text and images, the latter “Mats [matrices] for Newspaper Use” in publicizing local theatre appearances. One of the mats is Hirschfeld’s caricature, and the circumstances behind its creation are explained on page two:

CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION. You are about to sell an attraction which may be just a little different than those you have handled previously. You may encounter some difficultly in planting photographs in newspapers, for example. We have foreseen this obstacle and have prepared three or four suggestions which may be valuable to you in overcoming this obstacle.

- We have engaged an artist [Hirschfeld] to make an attractive caricature of Duke Ellington, one-column mats of which are available. Little objection ever has been voiced by amusement editors or radio editors to the use of this caricature in their columns. Many of the greatest metropolitan dailies in the country have used it.

Reading between the lines, Hirschfeld’s caricature was a work for hire, commissioned by Mills Dance Orchestras, Inc. -- a company owned and operated by Irving Mills, Ellington’s agent, manager and music publisher since the fall of 1926 -- to serve a specific need: providing an image of Ellington that editors at “the greatest metropolitan dailies” (i.e., newspapers written by and for whites) might actually publish, as opposed to a photograph that they wouldn’t. What objection could these editors possibly have to publishing a photograph of this handsome young man, one of America’s greatest musicians? Hint: the year was 1931, and Duke Ellington was African American.

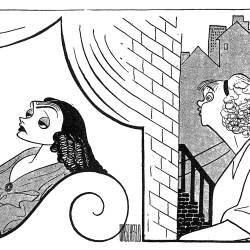

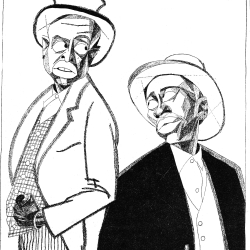

Note the similarities between Hirschfeld’s 1931 caricature and this publicity photo of Ellington, taken by the “De Barron Studios N.Y.” probably in 1929 (the earliest publication of the image I’ve found: The Baltimore Afro-American, December 14, 1929).

- The posture and expression are nearly identical. In the photo, Ellington faces the camera, and gazes deeply into the lens with open eyes and closed mouth. Were one to crop the photo to show only Duke’s head, we’d see a pose consistent with a standard driver’s license photo or mug shot. This is a pose seen relatively infrequently in the work of Hirschfeld, whose subjects usually look away from the viewer; when their gaze is towards the viewer -- eyes often shown as slits or beads -- their torsos are generally at an angle, not facing directly forward with eyes open as here.

- Compare the shape of the ears, nostrils, mustache, lips and chin line depicted in each image.

- In the photo, white dots are visible in Duke’s pupils, a reflection of the camera’s flash. The white dots are visible in Hirschfeld’s rendering as well, an apparent vestige of the flash that he elected to retain -- and exaggerate.

What these clues suggest to me: This was the photo of Ellington, or at least one of them, that the daily papers had declined to print. In response, Irving Mills sent Hirschfeld a copy of this photo with instructions to use it as the basis for a caricature. David Leopold, Creative Director of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation, interjects: “Although I think you are correct that Hirschfeld used the photo for details of his drawing, he would have been well acquainted with Duke and his music. I am confident he had seen him perform multiple times before he did this drawing, and he had already collected a number of Ellington 78s for his collection.”

In 1992, Hirschfeld was contacted by the Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition Service (SITES) who were preparing a major Ellington exhibition to open the following year. Did he still have the original artwork for the caricature? Unfortunately, he didn’t. (The present whereabouts of the original artwork aren’t known to me. Speculation: It may have passed to a descendent of Irving and Bessie Mills, who left five sons, two daughters and numerous grandchildren. Alternatively, I’ve been told that a lot of choice materials stored at Mills’s office were tossed out years ago, in which case Hirschfeld’s original may have would up in an icinerator, landfill, or somebody's attic.)

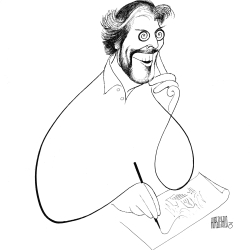

SITES supplied Hirschfeld with a less-than-optimal reproduction of the Ellington caricature, reportedly taken from an old issue of The Chicago Defender, most likely photocopied off a microfilm. Somehow, the date “circa 1927” was ascribed to the caricature, an obvious error since its earliest appearances in the Defender came in the May 23, 1931 city edition and the May 30, 1931 national edition. In September 1992, Hirschfeld re-drew the caricature from the reproduction. David Leopold notes that an edition of 190 lithographic prints plus approximately 20 artist’s proofs “was published later that year, and has proved to be popular.” (Copies of the 27” x 17” lithograph are currently available for purchase from the store on this website.) Hirschfeld’s hand-drawn original from 1992 is today part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collection, where it is cataloged as object “edanmdm:npg_NY780116.”

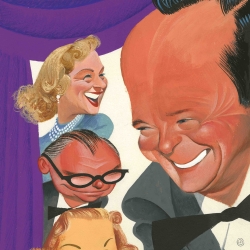

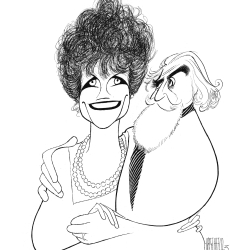

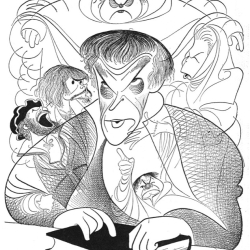

Hirschfeld would draw Ellington on multiple occasions in the decades that followed, but his 1931 caricature – and the 1992 re-draw – shows Ellington as Mills wanted him presented to the public, as a composer and bandleader of great consequence. There is a gravitas and intensity that I don’t find in Hirschfeld’s other portraits of the maestro, which depict a joyous entertainer in later years. All are wonderful, each in its own way.

----------------

Steven Lasker is an Ellington historian, researcher and collector who lives in Venice, California. He contributes regularly to a website dedicated to Ellington research presented chronologically and found at: WWW.TDWAW.CA