Cheryl Crawford

“The theater has been my life.” – Cheryl Crawford (1902-1986)

“Who, if I cried, would hear me among the angelic orders? Answer: Cheryl!” – Tennessee Williams

The history of New York theater is populated by extraordinary women whose names, sadly, may not be remembered today. No Broadway houses are named for them, yet the contributions to the theater of Theresa Helburn, Eva Le Gallienne, Margaret Webster, and, perhaps above all, Cheryl Crawford, had a significant impact on the art and business of theater and should be proclaimed and celebrated. Despite the lack of name recognition, Crawford’s mark on theater history remains profound and may be studied in her comprehensive archives at the Billy Rose Theatre Division of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

When Cheryl Crawford was in grade school, she missed the class where the students were taught the Pledge of Allegiance. As a result, she had to learn it by listening as other students recited it. In so doing, she mistook the line “one nation indivisible” for “one naked individual.” Decades later, after she had become an independent producer, she realized that the line was an apt one, for an openly gay woman “finite and vulnerable,” out on the barricades of the formidable commercial theater world. The phrase became the title of her 1977 autobiography.

The website of the now bi-coastal Actors Studio proudly proclaims that the institution was founded in 1947 by Cheryl Crawford, Elia Kazan, and Robert Lewis. It mentions that the roots of The Actors Studio go back to the Group Theatre (1931-1941), an organization founded by Cheryl Crawford, Harold Clurman, and Lee Strasberg. Of the latter group, Cheryl Crawford wrote, “We were a bizarre trio, two Old Testament prophets and a WASP shiksa.”

Born and raised in Akron, Ohio, by the age of eighteen Cheryl wanted “the hell out of the tame Midwest.” She enrolled in Smith College and was elected head of the Dramatic Association, where she selected Kalidasa’s play Shakuntala for her first production. Just before graduation, she discovered that the Theatre Guild in New York was starting an acting school. Although Cheryl already knew that she wanted to be a producer, she felt that enrolling in the acting classes would be the best entry into that prestigious organization. Her father was furious: “I can’t let you go to that wicked city!” Yet go she did, moving into an apartment at 66 Bedford Street in Greenwich Village. When the course was completed, the search for a job became urgent. She made the rounds, looking for work as a stage manager but discovering that “No producer seemed interested in a female stage manager. Or even an assistant stage manager. Or even a water girl. Females were actresses or nothing, it seemed.” Fortunately, Philip Loeb recommended her to take over his part-time job as casting secretary at the Theatre Guild, and she negotiated with Theresa Helburn, the Guild’s co-founder, for the additional position of assistant stage manager on the Guild’s first fall production. Over the next few years, Cheryl took on additional responsibilities at the Guild, before leaving to devote her time to the Group Theatre.

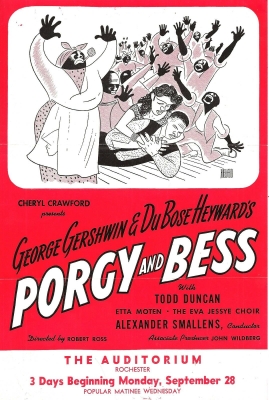

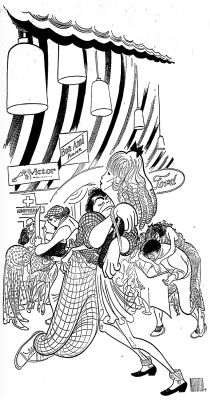

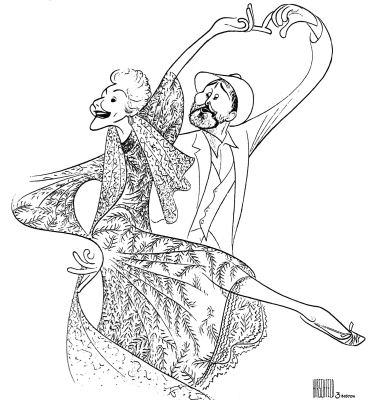

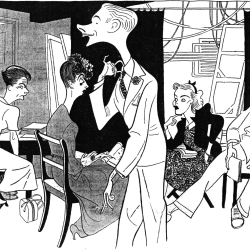

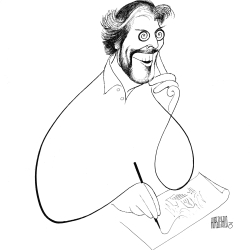

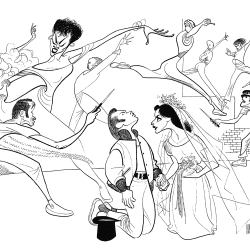

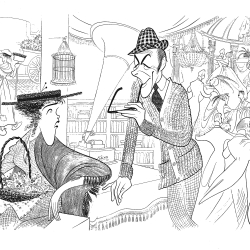

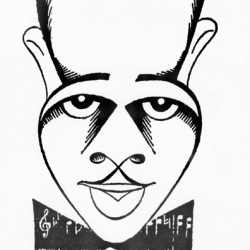

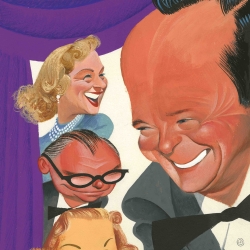

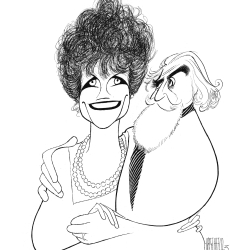

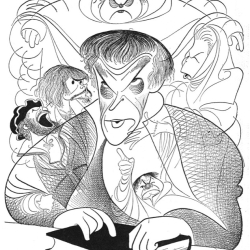

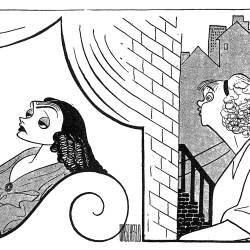

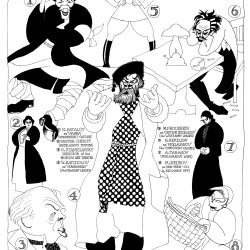

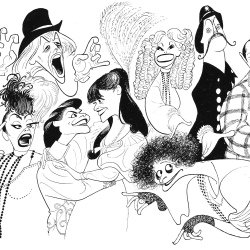

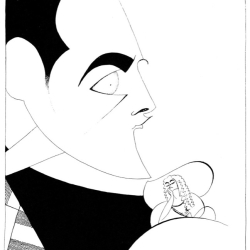

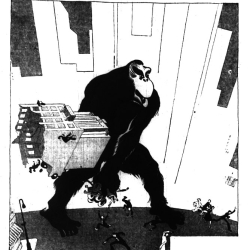

It was in the early 1940s, as an independent producer, that Cheryl Crawford’s productions first attracted the pen of Al Hirschfeld, with her revival of Porgy and Bess. The Theatre Guild’s 1935 premiere production had not been a financial success. In 1942, Cheryl had many of the recitatives cut, making the opera more accessible as musical theater. It was a great success and established Cheryl as a force in the theater. A year later, Al captured another Crawford Show: the Kurt Weill/Ogden Nash musical One Touch of Venus.

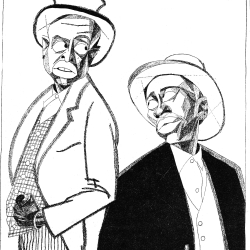

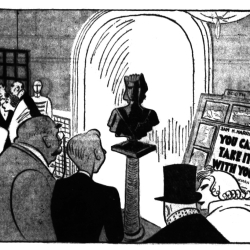

In the mid-1940s, Cheryl joined with her friends Eva Le Gallienne and Margaret Webster to form the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.), in a noble attempt at creating a nonprofit repertory company. Eli Wallach, who was in the A.R.T. company, affectionately referred to Cheryl as “a unique, courageous lady of the theater, forever stirring things up.” Anne Jackson has talked about Cheryl’s commitment to the “finding, training, and supporting of young talent.” Between 1946 and 1948, A.R.T. presented nine classic plays on Broadway.

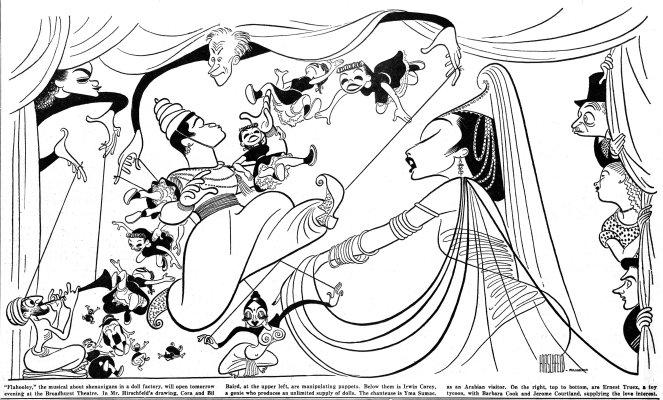

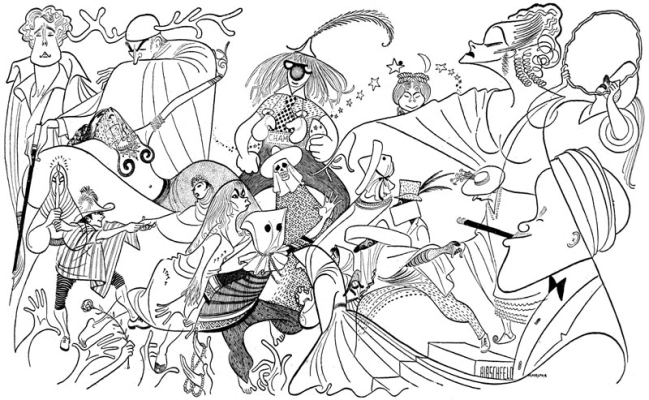

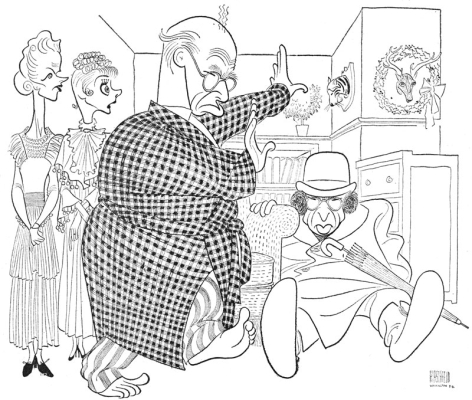

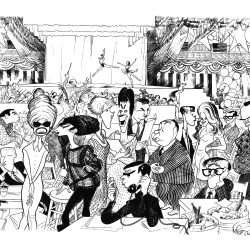

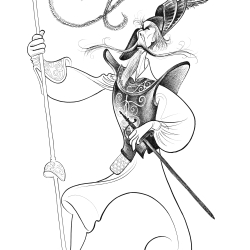

In the early 1950s, Cheryl had a huge success with Brigadoon. Her other musical productions during that period were Flahooley and Paint Your Wagon, both drawn by Hirschfeld. The period also inaugurated what was to be a fruitful, if not always financially successful, ten-year collaboration with Tennessee Williams. Cheryl produced four of his plays: The Rose Tattoo, Camino Real, Sweet Bird of Youth, and Period of Adjustment. Of the complicated and challenging production that was Camino Real, Cheryl wrote to Tennessee on April 30, 1953, “What can I say to you now except that I’m proud to have done it. I’d do it again knowing the outcome.” Tattoo, Camino, and Sweet Bird were captured by the pen of Al Hirschfeld.

Of Period of Adjustment, Tennessee wrote to Cheryl, “It’s a play that isn’t my best, by a long shot, but it’s nevertheless as honest a play as I’ve written. I’m putting my faith in the devoted way we all work together, so that even if we fail to score, we will have had a creative experience together, you and all of us, that will give us no reason to hang our heads in shame.”

In the Epilogue to her autobiography, Cheryl wrote: “Was I ever fully satisfied with a production? No, not entirely, but I tried to pursue excellence.” Ms. Crawford’s pursuit of excellence has given more to the American theater than just about any other “one naked individual.”

Alan Pally