Hirschfeld and Selma

With the release of the film, Selma, controversy has arisen about the interaction between President Lyndon Johnson and Dr. Martin Luther King in this landmark event of the civil rights movement. Former Johnson Administration domestic affairs chief Joseph A. Califano, Jr. has argued that the film unfairly portrays LBJ at odds with King and that Johnson himself helped engineer the Selma march. Director Ava DuVernay has countered that she was not interested in making a “white savior” film, and instead concentrated on the people who actually made the march. At times like these, one wishes that there was an eyewitness who could tell us what the conversation was between Johnson and King as the marchers approached the Selma bridge. Surprisingly there is, and even more surprisingly, it was Al Hirschfeld who was in the Oval Office when Johnson spoke to King at protesters approached the Selma bridge on the second day of unrest.

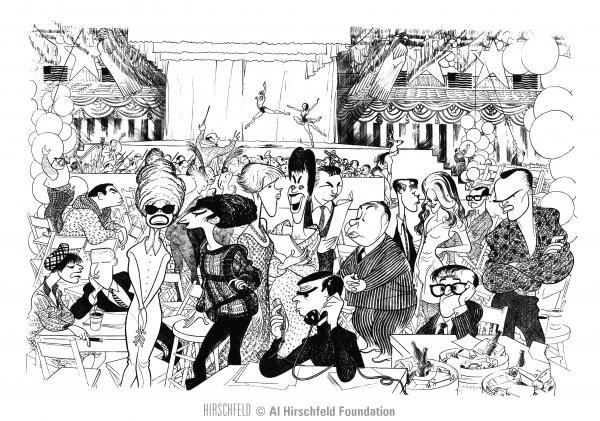

Hirschfeld had drawn a composite of fourteen performers who appeared as part of Johnson’s Inauguration in 1964 at the instigation of composer Richard Adler, who produced the event (and is also pictured in the drawing). Johnson was not a favorite of Al’s, “he impressed me as an affable drummer covering the southwest territory for a slick New York cigar manufacturer,” but he was persuaded by Adler and his own wife, Dolly Haas. Along with images of Alfred Hitchcock, Julie Andrews, and Carol Channing, all of who he had been drawing for years, were Hirschfeld’s first takes of Elaine May, Mike Nichols and Woody Allen, a trio of comic voices just emerging on the scene, whose biggest impact on American culture still lay ahead of them.

With the drawing completed and the President installed in the White House, the Hirschfeld family was invited to the Oval Office on March 9, 1965 so that Al could gift the new president with the drawing. He went reluctantly, not only out his tepid response to Johnson, but because a previous visit to the White House to meet Franklin D. Roosevelt to give him a drawing that appeared on the cover of The Nation in 1944 had made Al swear off meeting any world leaders. Roosevelt, who Al had revered, had appeared so decidedly human that Al concluded, “I was thankful that I never met President Lincoln.” The family was met by Johnson at the door to the Oval Office, who offered them a seat as his phone rang. Johnson put the call on speaker-phone and soon the room reverberated with his conversation with King, who was at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma with 2,500 supporters, but blocked by Sheriff Jim Clark, a wall of state troopers and the Klu Klux Klan. King said he was bent on crossing the bridge, even though two days earlier, in what would be called "Bloody Sunday”, when he tried, Clark and his minions had brutally attacked the civil rights group, leaving seventeen marchers hospitalized, one near death.

King wanted to confront the armed militia at the bridge and Johnson pleaded with him “I understand Dr. King, and please tell them that their President is with them in spirit…I can only advise them to hold the line and avoid the spilling of more blood. May God be with you.” Unbeknownst to anyone in that room, King and the leaders of the group had already decided not to cross the bridge that day, but Hirschfeld was impressed. As their fifteen-minute interview stretched into an hour, Johnson talked of the moral dilemma he faced in sending more troops to Vietnam as that war escalated. His military advisers insisted that he must do it to prevent more death, but Johnson understood that no matter what he did, at least politically, he would pay the price. Hirschfeld was so engrossed that he never took out his pencil to sketch the President. His opinion of the President would change, “the cigar salesman turned into that of a warm, lovable, and confused grandmother.”

Adapted from The Hirschfeld Century: Portrait of the Artist and His Age by David Leopold to be published in May 2015 by Alfred A. Knopf.